Reflections Along the Way

Travellers' Tales and Reflections on the State of the WorldHarnessing Diversity

Harnessing Diversity

How the coronavirus pandemic sheds light on humanity's greatest transformational challengeHomo sapiens has been hugely successful as a species. We may have evolved from other animals, but with the development of self-aware consciousness, we’ve transcended the limits of purely biological evolution. Through our unique abilities we’ve created the Anthropocene epoch on earth, full of amazing technological and artistic achievements. But in the process, we’ve brought about an ecological crisis that threatens the planet with serious damage and our own species with extinction. No, not the current pandemic, but rather the whole nexus of challenges that include climate change, habitat loss, biodiversity loss, environmental pollution, overuse of resources and growing inequality. What you might call the “human predicament”.

Materialist science on its own is not able to provide us with an answer to these challenges, since it tells us what we can do, but not what we should do. Religion on its own isn’t the answer, since it too easily asks us to fly in the face of known reality on the grounds of archaic belief systems and all-too-human power structures. And our social structures themselves seem to have led to civilisations and empires that aren’t yet able to provide the answer either, since our history points towards an inevitable pattern of rise and fall. There is a real danger that our combined efforts to avert catastrophe will turn out to be ‘too little, too late’.

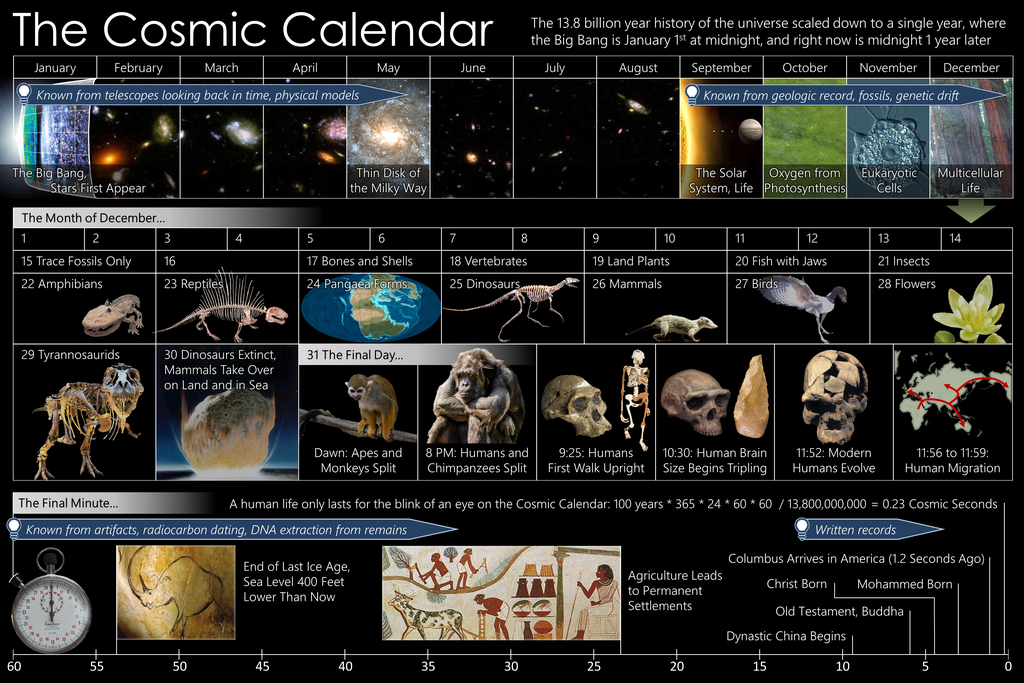

From what we now know about the evolving nature of the universe since its origins 13.8 billion years ago, we can discern a pattern of continual development, punctuated by a series of thresholds. Each threshold creates new possibilities and the accelerating development of more complex capabilities. The threshold of human self-aware consciousness has given rise in homo sapiens to a species capable of understanding the nature of the universe, our own place within it, and the strengths and weaknesses of our unique nature. We are also the first species with powers of creativity capable of matching or even surpassing those of nature. We are natural born learners.

But it seems that the same process of evolution that has brought homo sapiens these incredible gifts, has come packaged together with a dark side. We are a social species and have built societies that aspire to espouse values such as courage, compassion, co-operation, truth, loyalty and community. But we are also individuals, and these values all-too-often mask personal drives that are far less publicly praiseworthy. Motives such as selfishness, status-seeking, competition, deception, control and power.

Transforming cultural values is extremely difficult and calls for strong, united and skilful leadership. This is a lesson that has been learned by many organizations not only in the world of business, but also in in other fields such as religion, public administration and charitable activities. How much more difficult, then, is the task of transforming the whole of humanity, so that we are not constantly at the mercy of our dark, shadow motives?

The present coronavirus pandemic in which homo sapiens and SARS-CoV-2 seek to establish some form of mutually acceptable ecological balance is providing plenty of opportunity to demonstrate our ‘higher’ values at work: governments protecting individual lives rather than pursuing ideological purity; international co-operation between scientists; business competitors cooperating to develop potential vaccines and to produce vital equipment in short supply; whole populations honouring the service of those in previously taken-for-granted occupations.

But there are also signs of our darker side asserting itself in a variety of ways: playing the “blame game” rather than seeking to learn from our mistakes; politicizing the virus either nationally or internationally, rather than seeking to break down cultural barriers; increasing cases of online fraud in one form or another; spreading false rumours in order to inflame passions and encourage public displays of anger; even some elements of profiteering from people’s misfortunes.

As evolutionary scientists such as Edward O. Wilson of Harvard University, David Sloan Wilson of Yale and Kevin Laland of St Andrews have pointed out in recent best-selling books[i], humanity is evolving socially and culturally very rapidly indeed. But are we evolving fast enough in the face of the accelerating human predicament? The question is, can we turn our many differences into the most diverse community that humanity has yet assembled, and find ways of better organising how we live together on our finite planet? Ways that must incorporate the very best insights, wisdom and means of learning that science and civil society can assemble from people of all nationalities and all faiths and none. Surely, that is our supreme challenge if we are to make progress in the most ambitious and multi-faceted cultural transformation that humanity has yet attempted?

[i] The Social Conquest of Earth by Edward O. Wilson,

This View of Life: Completing the Darwinian Revolution by David Sloan Wilson and

Darwin’s Unfinished Symphony: How Culture Made the Human Mind by Kevin N. Laland

Coronavirus: How we talk about it

Coronavirus

How the language of human warfare masks the true nature of the present crisis.A leading article in ‘The Times’ of 13th April 2020 states, “Not for nothing has military language been applied to “front-line” workers in the past few weeks. They are saving their country and endangering their lives.” Indeed, much of the coverage of the coronavirus crisis uses military language. In his speech recorded after being discharged from hospital, the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, said that we are, “making progress in this incredible national battle against coronavirus. A fight we never picked against an enemy we still don’t entirely understand.”

It clearly makes sense to use such language. The situation around the world has much in common with times of war: the number of deaths; brave men and women, particularly in NHS and social care, putting their own lives at risk to save others; massive disruption to the lives of the civilian population; a state of emergency; deployment of armed services. Just like in times of war, alongside the heart-breaking stories of families losing loved ones without the usual comfort of final goodbyes, there is also much talk about ‘community spirit’. Television and social media are full of creative ideas of how people can help themselves and each other to cope with the disruption to their everyday lives.

It clearly makes sense to use such language. The situation around the world has much in common with times of war: the number of deaths; brave men and women, particularly in NHS and social care, putting their own lives at risk to save others; massive disruption to the lives of the civilian population; a state of emergency; deployment of armed services. Just like in times of war, alongside the heart-breaking stories of families losing loved ones without the usual comfort of final goodbyes, there is also much talk about ‘community spirit’. Television and social media are full of creative ideas of how people can help themselves and each other to cope with the disruption to their everyday lives.

The trouble is that however appropriate such language may be, it masks an important aspect of the crisis that needs more attention than it is getting. Particularly for the long term. A clue to this was provided in another article in the same edition of ‘The Times’ – this one about ending the lockdown in UK. Google and Apple have announced co-operation “at breakneck speed” to develop an app that will work on smart phones to allow contact tracing, Their representatives are quoted as saying, “There has never been a more important moment to work together to solve one of the world’s most pressing problems.”

Except that it isn’t “the world’s” problem – it is humanity’s. We are so used to equating ‘the world’ with ‘humanity’ that we don’t even notice the difference. But in terms of our military metaphors, it matters a great deal. Unlike all wars reflected in the language that is all around us today, this isn’t a battle for supremacy between nations of humans or the values that they stand for, this is a struggle for survival between two different species: homo sapiens and Covid-19.

Each is struggling for its niche in the ecology of life on earth.

The language of war isn’t totally inappropriate, of course. Like human warfare, struggles between species produce winners and losers – survival for the successful and extinction for those less robust. But as we have watched the daily evolution of the struggle in terms of the timelines of the numbers of tests, new cases, and deaths per day, each of the two protagonists – homo sapiens and Covid-19 – is calling on evolutionary resources that operate on a completely different timescale: different from the daily graphs, and different for each of the two of them.

Covid-19 suddenly appeared in humans in December 2019, the latest mutation of a coronavirus. It evolved in the way that biologists have understood increasingly well since Darwin first drew attention to it – natural selection by means of biological evolution. And viruses have been around for some 1.5 billion years. They are small, relatively simple organisms, and with a lifecycle measured in days, they evolve rapidly

Homo sapiens, on the other hand, has been around for only a few hundred thousand years, and being a large complex mammal with a life expectancy of 70 or 80 years, we evolve biologically very slowly. On the other hand, as evolutionary scientists such as David Sloan Wilson of Yale University and Kevin Laland of St Andrews have pointed out in recent best-selling books[i], humanity is evolving socially and culturally very rapidly indeed.

So, the two species involved in the present struggle, extremely different in terms of size and length of life, are also calling on different evolutionary resources: biological evolution versus cultural evolution. And that is the point that is being masked by the language we are using. It is hiding both an opportunity and a threat.

Our cultural evolution revolves around our adaptability and our inherent ability to learn. This is a characteristic that has been central to our species’ evolutionary success. We have developed resources such as language, written and visual media, the process of science and global communications each of which has supercharged the ability to learn that lies at the heart of what it means to be human. And there are many signs that the global scientific community is indeed working together to maximise our learning during the present crisis. That is the opportunity.

But in addition to exploiting this opportunity, we should beware of inadvertently succumbing to the threat. The threat that our military language reconnects us strongly with a more troublesome evolutionary characteristic that we have inherited – tribalism or “us versus them”.

Wouldn’t it be great if, using the ‘energy of crisis’ that is being inspired by both our present words and our actions for the common good, we could learn not only how to win the struggle against Covid-19, but how to prevent our own shadow side from holding us back?

Terry Cooke-Davies

13th April 2020

[i] This View of Life: Completing the Darwinian Revolution by David Sloan Wilson and

Darwin’s Unfinished Symphony: How Culture Made the Human Mind by Kevin N. Laland

Dialogue not Debate

We Need 'Dialogue' not 'Debate'

In a perceptive column in the Sunday Times on 5th April 2020[1], whilst lamenting what he calls ‘a deluge of recrimination’ about mistakes made by the UK government in its handling of the coronavirus pandemic, Matthew Syeed writes, “We need a rational debate now about charting a wise exit from the lockdown, about how to distinguish between people who have died with, rather than from, coronavirus, and about whether the government would benefit from new expertise, not least from industry, as it confronts unprecedented administrative challenges.”

Far be it from me to take issue with the winner of the Sports Journalist of the Year in 2016, especially when I am completely in agreement with the main point he is making: that to be indulging in a blame game under the present circumstances is “nothing less than a disgrace”.

But I respectfully suggest that what we need is less a ‘debate’, than a process of national and international dialogue. There is a big difference. It is true that both debate and dialogue are forms of structured conversation, but the purpose of a debate is to produce a victory for one point of view over another, and each proponent is encouraged to defend their own opinion whilst identifying weaknesses and flaws in their opponents’. In government and politics, it certainly leads to legitimacy for the winners, but it also creates losers.

Dialogue is very different. It encourages listening without resistance and explores underlying causes, rules and assumptions to get to deeper questions and framing of problems. In 1990, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology initiated the MIT Dialogue Project to allow dialogue to become a tool of practical use for organizations. In 1999 William Isaacs, its first Director, published “Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together”[2] making the impressive results public, and describing a process for transforming the quality of conversation and the thinking that lies beneath it.

The trouble is, the principles of ‘debate’ are woven into the fabric of almost every aspect of our everyday lives in UK: in parliament, in courts of law, in media interviews, in general elections – the list is extensive. “Dialogue,” writes William Isaacs, by way of contrast, “poses a paradox in practice. While it seeks to allow greater coherence among a group of people (note this does not necessarily imply agreement), it does not impose it. Indeed, dialogues surface and explore the very mechanisms by which people try to control and manage the meanings of their interactions.”[3]

Nevertheless, if we are to avoid the inevitable search for ‘winners and losers’ in the current ‘blame game’ around actions to tackle the coronavirus pandemic, shouldn’t we be seeking to transform the quality of our public conversations about it?

Terry Cooke-Davies

5th April 2020

[1] Matthew Syeed, ‘I challenge the online ‘experts’ so critical of No 10 on coronavirus: tell us, has Sweden got it right or wrong?’, Sunday Times, 5thApril 2020.

[2] Isaacs, William (1999) Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together. Currency. New York, NY.

[3] Downloaded at https://thesystemsthinker.com/dialogue-the-power-of-collective-thinking/ on 5th April 2020.

A Thousand Ages

A Thousand Ages

The Bible in its cosmological contextIn a well-known hymn dating from 1708, Isaac Watts wrote:

“A thousand ages in thy sight

Are like an evening gone;

Short as the watch that ends the night

Before the rising sun.”

He was definitely onto something.

Our generation is the first that has been able to tell the story of the cosmos (from its origins at the ‘Big Bang’ to the universe we know today) in a form that is substantiated by reliable scientific evidence.

In his book ‘The Dragons of Eden’ (1977) Carl Sagan, like Isaac Watts, contrasted two different perspectives on time. He used the concept of a “Cosmic Calendar” to express the entire timeline of the cosmos as a single calendar year, so that our human imaginations could more readily grasp the immensity of “deep time”. The diagram below, created by Efbrazil, illustrates the concept visually. According to this calendar, the time now is midnight on December 31st and exactly twelve months ago, in the first few seconds of January 1st, time, matter and the whole of reality came into being.

Sagan, of course, was writing for a general audience whereas Watts’ hymn was written to form a part of Christian worship. It isn’t immediately obvious to link the two. Yet making this connection opens up a perspective on the Bible and on the life and mission of Jesus that is highly relevant to our social, economic and political life today. (This is quite possibly also true of other great religions of the world today, but my own understanding is as a Christian who is also a social scientist and I am not familiar enough with other religious traditions to speak about them with any confidence.)

If we tell the story of Jesus’ historical significance in terms of the Cosmic Calendar, it sounds something like this:

“Imagine that exactly a year ago, in a single unique act of creation, the universe in which today we live, move and have our being flared forth into existence. Within a month the first stars had been formed, and by May galaxies such as our own Milky Way had developed. By September our own solar system had formed, including our home planet Earth, and soon afterwards the first living cells appeared. During October some cells on earth developed the ability to transform sunlight into oxygen, and thus capture the sun’s energy in forms that would feed and sustain life on earth. In the course of December, complex life as we know it came into existence, with the dinosaurs showing up on 25th, and bowing out on 30th, leaving space for mammals to thrive.

Our first human-like ancestors started to walk upright on the African Savannah at about 9.25pm on 31stDecember (today in our story). Shortly afterwards, by 10.30 this evening, our brains had roughly tripled in size as we began to live in much larger troops and our social relationships became more complex. Just a few minutes ago, between 11.56 and 11.59 we migrated out of Africa, and spread out all over the world. It’s during the last minute that things have become really interesting, with the pace of change becoming more and more rapid. 45 seconds ago the last ice age ended and 22 or 23 seconds later, we first learned how to farm crops and domesticate wild animals. This allowed us to live in permanent settlements, complete with elites and surpluses of resources. Eventually, this even led to writing, culture, city-states, civilisation, kingdoms and empires.

Six seconds ago, in Palestine, the people of Israel began writing the scrolls that would end up as the Jewish Bible These recorded their quest to understand their relationship with the creator of all reality, and what it all meant. Among them were prophets, who warned that the social injustice embedded in humanity’s way of life would have catastrophic consequences. About two seconds later, a young Jewish teacher and healer named Jesus scandalized society by mixing freely with groups of previously excluded people. He even kept table fellowship with them, embodying, as he himself described it, the creator’s love for all his creation. He recognised that he posed a threat to the fabric of society and warned his followers of the inevitable response: the powers-that-be would execute him for leading the faithful astray and for preaching sedition against the Roman Empire. And that is precisely what happened. He had become a ‘scapegoat’, sacrificed to maintain the cohesion of society.

Surprisingly, that wasn’t the end for his followers. They experienced Jesus raised up to new life, as a sign that he had been vindicated by the creator. So vibrant was their faith, and so persuasive their new way of life, that even the Roman Empire itself adopted this new set of beliefs as the State’s official faith. By doing so, the church became enrolled into a life of hierarchy and inequality similar to that which the prophets and Jesus had protested against so strongly.

During the final seconds of our year these warnings have continued to go unheeded. Not only that, but the development of science-driven technology has enabled human empires to flourish and grow at breath-taking speed. Humanity has filled the whole earth to its full capacity. Our commercial and national empires now wield such massive technological, military, commercial and social power, that they are depleting the earth’s store of limited resources much faster than they can possibly be renewed or replaced. So fast, in fact, that they are threatening the earth’s ability to support and sustain the human species. Physical evidence from scientists has now been added to the social warnings of the prophets and Jesus. Humanity’s neglect of social justice, personal wholeness and ecological integrity is now threatening humanity itself if not with extinction, at least with an enforced loss of much of the way of life that we all currently enjoy.”

This way of telling the story sheds light on the Christian scriptures themselves in the light of an evidence-based story of cosmic development, rather than narrating the story of creation from the viewpoint of scripture. It turns the story inside-out, but unlike the stand-off between fundamentalist Christianity and militant atheistic scientism, it provides a ‘meeting place’ where Christianity and Science can talk to each other in constructive dialogue. It also recognises the shared interest that both Christians and secular society have in talking constructively to each other about the relationship between humanity and the rest of the earth community.

It may well be that such a story will be strongly resisted, both by the church who will measure it against the yardstick of ‘divinely inspired scripture’ and by a secular society which has a habit of shrugging off unwelcome warnings. After all, we place great faith in technology’s ability to solve even the most challenging problems, and there is a widely held view that religion itself contributes to society’s problems,

The need for a dialogue involving the whole global community has never been more urgent, and surely such a dialogue should incorporate the very best insights from all sources of knowledge and wisdom. If we can’t or won’t bring such a dialogue about then I fear that humanity’s brief reign on earth when seen against the “thousand ages” of the cosmos’ existence, may turn out to be a very short “evening gone” indeed — quite possibly followed by a nasty hangover.

A New Story

We Need a New Story

About Why Jesus and the Bible Matter to the WorldThe first book of the Bible gives an account of the creation of the cosmos and, ultimately, humankind.

We now have empirical evidence that the cosmos came into being some 14 billion years ago; that galaxies and stars emerged from the initial particles; that Earth and our solar system emerged from the death of a star; that life emerged from the Earth; and that humankind evolved from the earliest forms of life.

The Bible was written only after humankind had discovered agriculture, which in turn permitted the emergence of civilisation and empire, and human exploitation of not only other human beings, but of all living and inanimate resources to which we had access. Modern technology has increased the human ability to exploit other people and natural resources to such an extent that we are in danger of extinguishing the cradle of life itself.

Early in the development of empire, Jesus understood how the Bible pointed to the central need among humankind to care for each other and for all of creation. In his life he demonstrated the power of love and exemplified how to live free from all exploitation. His followers, convinced by the resurrection of the correctness of Jesus’ understanding, took up the subversive message, and the most successful territorial empire known to the Western world at that time – the Roman Empire, which had executed Jesus – first tried to subdue it, and finally subverted it to its own ends. This has been happening in the West through succeeding historical periods and different empires ever since.

In today’s world, when scientists tell the story of the cosmos, they locate human beings as a “rational animal” that emerged almost by accident from the random activity of inanimate matter – which provides us with no ethical guidance except for self-preservation. This is, however, the most widely accepted story reflected in the mainstream news media and education.

When churches tell the story of humankind in creation, on the other hand, they tell a different story: one based on divine revelation made accessible through the Bible. They focus on “man created in the image and likeness of God” – which leads to our projection of all kinds of human characteristics onto the creator – so that the very word “God” is coloured by anthropocentric thinking and people choose to worship the God they are most attracted to, or reject the notion of any ultimate creator to whom humankind is responsible.

Neither of these stories is universally accepted, even within the West.

Thomas Berry (1914 – 2009) argued passionately that we need a New Story that provides a shared meaning for humankind of whatever faith (or none) to pursue their own different activities as fruitful and responsible members of the earth community.

Shouldn’t all Christians who care about our world, our friends and our families be adding our voices to this plea?

Hearing Christ in Context

Humans like us (Homo Sapiens Sapiens) first appeared on earth some 200,000 years ago. For the first 190,000 years or so of that time, they lived in small tribes of hunter-gatherers as their ancestors had done for millions of years before them. These people, our direct ancestors, were highly dependent on their local environment, and their rhythms of life were closely attuned to those of the earth. They were nomadic and would probably have organized their lives so as to maximise the chances of the tribe’s survival, with people contributing according to their abilities.

The agricultural revolution and the invention of writing changed all that. Farming allowed for a surplus of food to be created, and cities developed in river valleys where increasing numbers of people were able to live off this surplus food. This is where elites began to emerge, and privilege became something to be enjoyed by those who had it, and aspired to by those who didn’t. As symbolic consciousness (writing and art in all its forms) developed a way of learning much faster than the slow changes to DNA, so cultural evolution in human society overtook biological evolution in our genes.

As cultures evolved, increasing concentrations of people in larger and larger cities led to both the creation of empires and a rapid and accelerating growth in human population. Mesopotamian empires such as Assyria and Babylon, Egypt under the Pharaohs and later the extensive empires of Alexander the Great and the Roman Empire.

Jesus was born at a critical period in the development of the Roman Empire. He spoke from the point of view of those who lost out under empire, he told the story of the dark side of privilege and empire, highlighting how it always pitted “us” against “them”. He exposed the underlying institutional violence that was held in check by the ‘scapegoating’ mechanism, and by his death exposed sacrifice for what it was. He talked about and embodied a design for humans to live together that was utterly different from the taken-for-granted design that fuelled empire and privilege, recognizing how hard it was since it conflicted with basic aspects of human nature. He showed how love for the creator of all life, for our fellow humans and for ourselves provides the antidote to the seductive attractions of privilege and empire.

The early church ‘got it’. The resurrection of Jesus when all appeared lost gave them the confidence that Jesus was right, as we can tell by reading the New Testament in the chronological order in which it was written. Particularly the Book of Revelation, difficult as it is to read in today’s very different culture, warns Christians against the dangers of being coerced by empire’s violence or seduced by the comforts of its expansive commerce.

This was a highly subversive and counter-cultural message, which is why Christians were from time to time persecuted by Roman emperors, who recognized the threat. Within a few hundred years, however, it was the church itself that became subverted by empire and privilege. And so we lost the authentic voice of Christ: first within the church as an institution endorsed by the Roman Emperors after Constantine, then within the full-blooded spread of Christendom with its bloody suppression of all doubting or dissenting voices, and finally by the modern culture of consumerism, built on the foundation of a technology originating from a worldview of ‘deterministic realism’ that understands reality to be composed of inert, mathematically predictable matter.

Today, however, humanity itself poses the biggest threat to life on earth. Alongside the many benefits that our cultural developments have brought us since the agricultural revolution, there has been a darker side. Overpopulation, overexploitation of natural resources, climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution and growing inequality are all problems created by humans and the cultures which we have evolved. Einstein is reputed to have said, “You cannot solve a problem using the thinking that created it.” Science and technology alone cannot save us – our culture must also evolve beyond one that enshrines privilege and empire at its heart. That is why it is important for humanity as a whole to hear the authentic voice of Christ: it is too important to be simply the preserve of the church.

We now understand the origins of the universe, the earth and life better than we did 2,000 years ago. So if Christ’s authentic voice is to be heard, it must be believable. It must be heard in the context of a story that holds up in the light of scientific discoveries, supported by evidence that withstands scrutiny. Which is why we can no longer see science and faith as opposing each other, and why serious attempts to understand both the wisdom of religions (including but not restricted to Christianity) and the evidence of science such as Yale University’s ‘Journey of the Universe’ should be embraced by Christians. They provide an important context for sharing the authentic voice of Christ with the world.

Nothing’s the Same Since Samos

Two places called Samos

On 5th April 2019, whilst walking the Camino of Santiago, I spent the night at a village called Samos, home to the oldest monastery in Spain. A visit to the monastery made a deep spiritual impression on me and inspired me on my return to England to undertake a series of spiritual reflections.

Three weeks later, on 26th April, whilst actively reflecting on how best to make sense of the spiritual impact that the Camino had on my life, I came across a film made on the Greek island of Samos by Yale University. It is called “Journey of the Universe” (JOTU), and it has transformed my understanding of Christianity and of the world in a way that the Greeks would call ‘metanoia’ – a word usually translated as ‘repentance’ in the New Testament, but which more properly means ‘change of mind’ in a transformative sense.

During the following week I devoureda six-week course of study from Yale Universitythat goes into the science behind the film and it was as if many disparate parts of my life were suddenly connected in a way that made perfect sense. For me it was one of those moments when everything changed, and nothing can ever be the same again.

Two alternative worldviews.

In my sermons and in each of the Bible studies that I have prepared up to now my attentionhas been focused on seeking to understand the church’s interpretation of the Bible and its implications in the light of the latest understanding of the world through science and social science research

In effect, promoting dialogue between two very different worldviews.

- Christian, with its focal lens as the person and teaching of Jesus, authenticated by divine revelation through the Bible, the teaching of the church and/or personal revelation to individuals (the action of the Holy Spirit)

- Secular research, with its foundations in human symbolic communication and the scientific method of assessing the truth or falsity of theories and other claims to the truth.

An inquiry lasting 70 years and counting…

As I reflect on this focus, it seems to have emerged almost naturally out of the very core of my being. At school, I was fascinated bymathematics and physics which quite naturally led me to study electrical engineering at University.

A profound spiritual experience at University in 1960 was understood by both the Church of England (my local vicar, the Bishop of Southwell and finally CACTM) as a ‘call’, and I became an ordinand and obtained my BA in Theology in 1965.

It became clear to me during my second year of theology studies that nothing in the New Testament made sense except through the lens of Jesus’ resurrection, and as an engineer and unquestioningbeliever in the power of science, I could not accept the resurrection as a fact. This prevented me from going forward for ordination and led me into a career that startedas a Biblical archaeologistandmoved on to become an entrepreneurwhen the six-day war between Israel and the Arab nations in 1967 brought that particular career to a close. From my early experiences as a young entrepreneur, I matured into abusinessmanand later a management consultant, in which role I obtained my PhD in project management. As a consequence, I found myself also involved with several universities as a social science academic.

With the benefit of hindsight, however, I can see that throughout my career I have never stopped trying to answer the question that I had first asked myself as an unhappy 7-year-old playing with my toy cars in the dust of the boarding school playground, “What’s it all about?”

This has involved reading and studying widelyin the worlds of both religion and science, seeking to reconcile the two apparently contradictory worldviewsof on the one hand science and technology and on the other the Christian faith.

In 1987, after seeing a TV programme series called ‘The Day the Universe Changed’(Burke 1985), reading a book called ‘Supernature’(Watson 1973), and having extensive talks with a client who was a devout Roman Catholic, I felt able to live ‘as if’ the Christian worldview was true, and a year or so later started attending a United Reformed Church regularly. Ayear or two after that I was ordained an Elder.

At the request of this church in 2003/4 I undertook a further course of study and was commissioned as a lay preacher. From that point onwardsevery time I prepared a sermon, or embarked on a course of discussion or study, my focus was on reconciling the two very different worldviews of science and religion.

The two worldviews combined into one

‘Journey of the Universe’tells the story of creation, from the beginning of our Universe to the present day. It does so in a way which conforms to everything that we currently know about the cosmos, the solar system, the earth, life and humanity but woven into a single story. It incorporates an account of the ‘impulse to creativity’ built into creation at every level, and it recognises the impulse of humanity not only to accelerate this creativity, but to understand our place in the universe through differing ‘lenses’drawn from science, social science, and the humanities (art, music, poetry, drama etc.)

In the book that accompanies the film, the authors write, “We are the first generation to learn the comprehensive scientific dimensions of the universe story. We know that the observable universe emerged 13.7 billion years ago, and we now live on a planet orbiting our Sun, one of the trillions of stars in one of the billions of galaxies in an unfolding universe that is profoundly creative and interconnected. With our empirical observations expanded by modern science, we are now realizing that our universe is a single immense energy event that began as a tiny speck that has unfolded over time to become galaxies and stars, palms and pelicans, the music of Bach, and each of us alive today. … … The great discovery of contemporary science is that the universe is not simply a place, but a story — a story in which we are immersed, to which we belong, and out of which we arose.

… … This story has the power to awaken us more deeply to who we are. For just as the Milky Way is the universe in the form of a galaxy, and an orchid is the universe in the form of a flower, we are the universe in the form of a human. And every time we are drawn to look up into the night sky and reflect on the awesome beauty of the universe, we are actually the universe reflecting on itself. And this changes everything.” (Swimme and Tucker 2011)

For me, that is exactly what it has done. It is far too early for me to know how these changes will work out in my life. But some changes are already happening – I have joined the Foundation for the Economics of Sustainability (FEASTA), started buying and eating less red meat, started reading books like “Rules for Revolutionaries” and “Who Owns England?”, downloaded Pope Francis’ Encyclical “Laudate Si’ – On Care for our Common Home.”

For several years now, I have argued that humanity is in desperate need of a common ‘moral compass’, although I could see no route that stood any chance of bringing one into being in the face of diverse worldviews, shared human nature and the perpetual problems caused by “us versus them”. What JOTU does is provides a shared motivation, underpinned by the best science available, for humanity to rise to our responsibilities as the only members of the earth community with conscious self-awareness. From now on, drawing on insights from the Bible and church teaching, from sciences, from social sciences and from humanities, that will be the new focus for my reflections in sermons, Bible studies and Blog posts.

Terry Cooke-Davies

Folkestone, Kent.

References

Burke, J. (1985). The Day the Universe Changed. London, UK, British Broadcasting Corporation.

Swimme, B. T. and M. E. Tucker (2011). Journey of the Universe. Yale, USA, Yale University Press.

Watson, L. (1973). Supernature: The Natural History of the Supernatural.London, Hodder and Stoughton.

After the Dust Has Settled

On 28th March 2019 I set out on an unlikely adventure for an old bloke like me, to walk the 170 miles from Astorga to Santiago de Compostela. I’m not totally sure why I wanted to do it: it had something to do with Lent; it also had something to do with seeing whether I could; and it certainly had to do with raising money for the Folkestone Rainbow Centre. When I returned home on 13th April in one sense nothing much had changed, but in another sense, everything had.

During the intervening fourteen days I had spent a day at the beginning walking around Madrid, and a day at the end looking around Santiago, with the remaining 12 days being taken up with 63 hours of walking – some of it idyllic and peaceful, some of it tough and challenging. The journey started and finished in warm sunshine, but in between there had been strong headwinds, rain, sleet, snow and fog. It involved climbing over 5,500 metres in all, and descending over 6,000.

There are many different pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela, with perhaps the best-known starting in France at Saint Jean Pied de Port, which is the route used for the 2011 film, “The Way”. This Camino Frances. as it is known, has been followed by pilgrims for over 1,000 years, and involves a gruelling 500 mile hike starting with a tough haul across the Pyrenees. The picture on the right shows a statue in Astorga of an old-time pilgrim, giving an impression of just how tough the pilgrimage must have been before the advent of modern equipment and clothing.

Mine was a much more modest version, chosen to be a challenge that could be completed within two weeks, and was manageable to an aging frame like mine. at 170 miles, it was considerably less challenging than the full 500 mles, but considerably more challenging than the most popular route of 70 miles starting from Sarria.

So now that two weeks have elapsed for the dust to settle, I ask myself what am I left with? I lost a pound or two in weight, and a few inches in size; I am still limping slightly from a torn muscle in the region of my right hip; I have a gallery of several hundred photographs; and I have made a few new friends in person and on Facebook.

More significantly, perhaps, are the echoes that I am left with of some profound spiritual insights. Each evening, I would read a chapter from Brian Zahnd’s wonderful new book, “Postcards from Babylon: The Church in American Exile.” But although the title speaks of America, the book speaks just as provocatively to anyone trying to follow Jesus faithfully anywhere in the developed world today.

Then, each morning as I walked the open miles between town and village or hamlet, I would ponder the implications for my own life and for churches in my home town of Folkestone. I plan to let these crystallise ove the next few weeks and months, and encapsulate them into posts on this Blog. Inspired by Brian’s “Postcards” I am also embarking on the preparation of a new series of Bible studies on the Book of Revelation, whih will be made freely available on this web site, alongside the three series that are already available: Genesis, the Psalms and Current Issues.

The physical adventure may have lasted only two weeks – but I suspect that the spiritual, intellectual and emotional adventure still has many months or years to run yet.

“Buen Camino”.

Reaching for the Heights

This is just one of the great views of Folkestone from the cliffs near Capel on one of my recent training walks. My training is all focused on a personal pilgrimage (or Camino) from Astorga to Santiago de Compostela, that I am due to start on 31st March and complete on 12 April. The problem is that, even today with less than two weeks to go, the UK government still has no idea whether or not Brexit will be happening on 29th March, and if it is happening, how orderly or otherwise it will be.

Tempting as it is to blame the government, or Parliament, or particular public figures arguing vehemently for one point of view or the other, the truth seems to me that democracy in any form can only work when the people, as a whole, arable to live with a shared view of what they can all tolerate, and with Brexit, that seems not to be the case. The country as a whole is roughly evenly divided as to whether or not we are better off socially and economically as members of the EU, or as an independent nation state. And if the people do not know what they want, then how can the Government, or Parliament, or anyone else deliver it for them?

Against this massive problem, the timing of my own long walk seems simple – and I have resolved it by booking a flight to Madrid for 28th March and then taking a bus to Astorga from Madrid on 30th ready to start walking on 31st. That seems to me to be the lowest risk strategy in the face of the continuing uncertainty.

Terry Cooke-Davies

Folkestone. 10th March 2019

Recent Comments